Thank you for spending a few minutes with my substack, Tim Gilmore’s deadpaper. I’m grateful for all readers, paid or otherwise. Becoming a paid subscriber here is one of the best ways to support my writing, if you can, and if you consider it worthwhile.

I encountered, this afternoon, a very Jacksonville kind of thing. I showed up at a “Jax Music History Workshop” hosted by the Downtown Investment Authority and spoke to artists charged with creating a “Music Heritage Garden” that reflects the city’s musical history, only to discover they had never heard of Ma Rainey, Blind Blake, Jelly Roll Morton or apparently Ray Charles or the Allman Brothers Band.

The email from the DIA said, “This hands-on workshop is your chance to share your knowledge and insights about Jacksonville’s vibrant music history and contemporary music scene. You’ll hear from the artists and participate in interactive workshop stations.” Fantastic. I’ve researched and written so much, and I’m bursting, nearly always, with ideas.

I’d love to talk about what poems Paul Laurence Dunbar wrote in Jacksonville, which ones John Rosamond Johnson set to music here and where Dunbar and Johnson gave public performances. Or about which Jacksonville streets gave their names to the titles of Blind Blake songs – “Ashley Street Blues” and “Stonewall Street Blues,” and which women Blake lived with on either side of Stonewall.

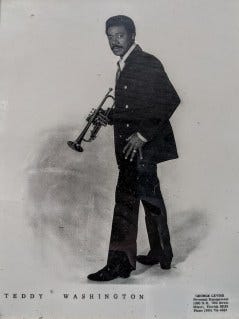

About how bassist Berry Oakley lived above the Handy Dandy Grocery with Linda Miller, before the Allman Brothers Band formed, when he was still with the Second Coming. About how Cannonball Adderley bemoaned the demise of LaVilla with Teddy Washington, who’d grown up there, played trumpet at Buster Ford’s Birdland on the Eastside and gone on to play with James Brown and Dizzy Gillespie.

So I showed up. I saw my friend Mitch Hemann, brilliant and knowledgeable archivist at the Ritz Theatre and Museum, and Michael Ray Fitzgerald, who wrote the book Jacksonville and the Roots of Southern Rock. So far, so good. So what were all these big blank maps and colored dot stickers all over the place? What were we doing? Where were the artists?

So I met a nice young woman with a Québécois accent from the “artist team” called Daily Tous Les Jours. How was this workshop supposed to work? What musical history were they focusing on? I was told I could take some colored dot stickers and place them on parts of the map where I liked to listen to music.

Confused, but still game, still thinking this was, according to the DIA, my “chance to share [my] knowledge and insights about” and so on, I mentioned the Riverside Music Tour, which happened last October, centered on several stages and locations around my home neighborhood and including live music in Willowbranch Park to riff off the “be-ins” that happened there in the late ’60s, where local bands like the Second Coming, Wapaho Aspirin Company and Cowboy played, with musicians like Berry Oakley and Reese Wynans (who both went on to the Allman Brothers Band), and Richard “Hombre” Price (who’d later play for everybody in Nashville), and Larry “Rhino” Reinhardt (who’d play with Iron Butterfly), and so on.

Mitch talked about the regional importance of the music that originated here, then mentioned the legendary Beatles performance during the remaindered winds of Hurricane Dora in the Gator Bowl, the “first Elvis Presley riot” and how “Heartbreak Hotel” was written in Jax. The very nice French Canadian tried to connect these stories to places on the map where we could put colored dot stickers. She seemed confused about whether Riverside were LaVilla or the Eastside were Riverside.

I don’t mean to pick on her, on Ariane. I don’t know Daily Tous Les Jour’s work at all, though I’m sure I should have looked it up afterward. I don’t mean to sound provincial; I’ve been to Montreal and Quebec City. I’d love to see Jacksonville artists connect to artists from anywhere else in the world on such a project. And maybe I’m being not just unfair, but wrong.

Maybe by this spring, when Ariane said her team had to submit their proposals, they’ll have read Galadrielle Allman’s gorgeously elegiac Please Be With Me: A Song for My Father, Duane Allman and Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff’s The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American Vaudeville, 1899-1926 and Peter Dunbaugh Smith’s Ashley Street Blues: Racial Uplift and the Commodification of Vernacular Performance in LaVilla, 1896-1916.

Maybe they’ll have listened to the music I write about (even if they haven’t read my stories) at JaxPsychoGeo, like Butler “String Beans” May and Blind Blake or Padrica Mendez’s opera career or Gram Parsons’ time rebelling against the Bolles School or Jelly Roll Morton’s loss of both his girlfriend Stella and his one blue suit in LaVilla.

And maybe what they produce will brilliantly reflect the musical history of this town for its “Music Heritage Garden.”

But one of the many things that has always driven me crazy about this bizarre hometown of mine is that it so often seems unaware of itself, uninterested in knowing itself, incapable of telling its own story. Is that three things? If it is, they’re bound together.

Part of it stems from its working-class history, its poverty, its low education levels. Part of it is regionally cultural, from its long having been “the capital of South Georgia.” (It fascinates me that the city had large numbers of residents born in the North and that even James Weldon Johnson wrote that it once was “the most liberal town in the South,” but that somewhere around the time the Ku Klux Klan was reborn in Stone Mountain, Georgia in 1915, more Jacksonville denizens had been born in Georgia than in Jax. The Southern Gothic novelist Harry Crews said Jacksonville was where Georgia went when the crops failed.)

I tell my students that the root verb of “ignorance” is “ignore,” that not only is ignorance not bliss, but that knowledge is a responsibility, that just as Polish historian Leszek Kołakowski says, “In politics, being deceived is no excuse,” James Baldwin writes, in The Fire Next Time, “It is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.”

Well, for whom am I writing? In this little rant, I’m writing for me and I’m writing to (and I hope “for”) you. So thank you for listening to me kvetch. For someone who wants to write a town’s life inside out, Jacksonville is perfect. So many of its stories lie discarded across the landscape, waiting. It’s almost embarrassing. Then again, if “what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas,” the same has always been true for the capital of South Georgia, if for completely different reasons.

Your title says it all. For reasons I don't understand (probably because I'm a native and cannot be objective), Jacksonville seems to have always had a problem marketing itself or acknowledging that there's anything here people would want to see or learn about. It's like at some point, a pall was spread over the city and people try and crawl out from under it in spurts and waves but can never quite manage.

When the history one lives is not their own.