Thanks for visiting Tim Gilmore’s deadpaper! So far your subscription to this semiweekly thingamabob gets you stories of alligator chandeliers and motel murders and the intro to my newest long-term historical project, Bootleggers’ Nightbook. For years, I’ve been writing about the two men I write about here, Emmett Tookes and Phil Gilmore, both of whom haunt me and dictate much of my writing. I hope you’ll keep reading and see why.

Click here for your tickets to the upcoming book launch of The Culture Wars of Warren Folks.

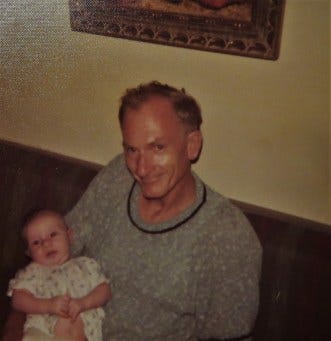

They’re hard to find traces of, these men. Though I heard stories about them both for 45 years, nothing surfaces for Emmett Tookes, just a few scattered records for my Great-Uncle Phil. Yet even in my father’s final years, as he suffered from congestive heart failure, he spoke of them. His memory only began to fade that final year, 2019, when he was 95 years old.

About which man I first heard, I don’t know, nor how old I was. They both seem always to have been there, in the shadows before me, reaching forward from alien depths, demanding I come to terms with them.

Click here for your tickets to the upcoming book launch of The Culture Wars of Warren Folks.

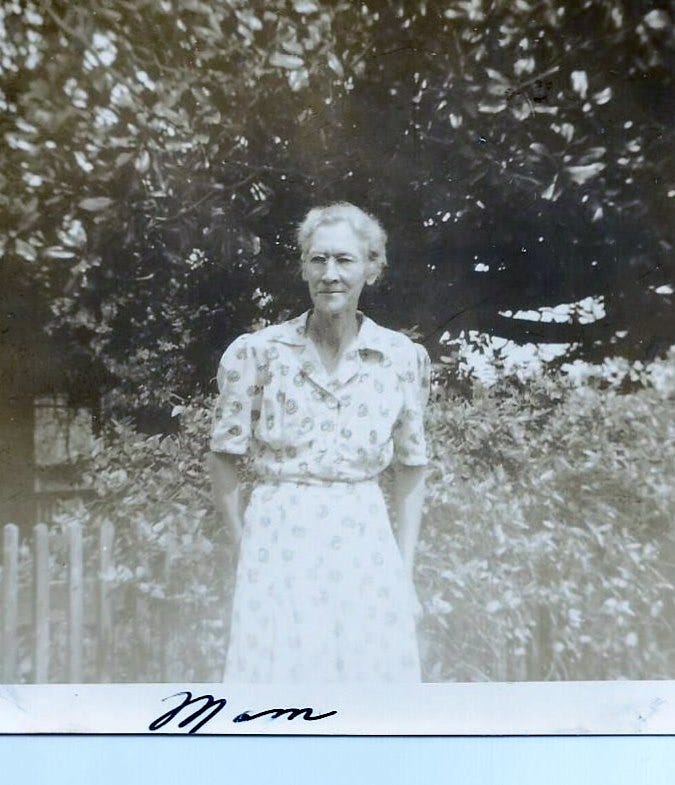

Emmett Tookes was, in my father’s words, his father’s “best friend” and “right hand man,” a black man my paternal grandparents, Grady and Pearl, fed dinner on the back porch while they ate with their children at the table indoors. Phil Gilmore was my father’s uncle, a white police officer who killed a black man in Macon County, Georgia, probably in the 1920s.

As a little boy, I felt about both men the way my father clearly felt in telling of them. At some point, of course, the foundations started to shift. Something wasn’t right. Something, I began to understand, had always been so very wrong.

Though my father never knew how many siblings he’d had, he told me his daddy, Grady, was one of five brothers, some of whom he’d never met. Grady died of a heart attack, 46 years old, in 1938, 36 years before I was born. Phil was my father’s favorite uncle. “He was a night watchman in Oglethorpe,” he told me in 2015, “and he was some kind’a police officer in Americus for a while and he did some farmin’ too.”

Macon County, Georgia contained the towns of Montezuma, Ideal, Marshallville, the now vanished Englishville, and Oglethorpe. My father grew up on a farm outside Oglethorpe, the county seat, Americus one county over. President Jimmy Carter was born the same year as my father, 30 miles away, another peanut farmer. They were so much alike; my father hated him. That’s a later story.

Emmett Tookes worked for Grady Gilmore for years. Four years before my father’s death, I interviewed and recorded him every Saturday morning for three months, existentially needing to solidify some final version of stories I’d heard all my life and to excavate new old truths. Tookes, he told me, “helped with anything that had to be done. Killing hogs. Putting up fences. Working the crops.” They grew corn and beans. The “money crops” were cotton and peanuts. “They got along real, real good. He was my daddy’s right hand man.”

Then come strange contradictions. “They were friends, absolutely,” my father said. “He was my daddy’s best friend, but he did not eat dinner with the family. When my mother fixed dinner, she fixed him a plate, just like she fixed us a plate, and he ate off to himself, outside or on the porch.”

Then that omnipresent qualifier: “I didn’t have much feelin’ about it, that’s just the way it was, and that’s just the way everybody acted back there then.”

Remembering his Uncle Phil, my father said, “He came to visit us pretty regular and took an interest in us. He rode a motorcycle and I remember one time he said, ‘You have to be careful.’ He said, ‘This thing’ll dump you off in a minute.’ And he said he’d never killed but one man in his lifetime.”

Click here for your tickets to the upcoming book launch of The Culture Wars of Warren Folks.

I’d heard the story dozens, maybe hundreds of times growing up. That Saturday morning, eight years ago now, my father told it this way: “My Uncle Phil went to arrest this big black man. I’m not sure if this was in Americus or Oglethorpe or somewhere else. Somewhere in the county there. They had an arrest warrant for him. It was his job to arrest him.

“So he went to arrest him and the man grabbed his gun. He wore it on his side, you know. He grabbed my Uncle Phil’s gun, wasn’t gone let him arrest him. So he grabbed the midways of the gun, and when he did, Uncle Phil came around with his hands, and he grabbed the butt part and the barrel. So the black man had it in the middle and my Uncle Phil had two hands on it. So they wrestled around it for a while and he managed to get it pointed toward the black man, and when he did, he, the barrel was in his hand like this, and when he did, when he got it pointed toward him, he pulled the trigger. And the bullet burned his hand comin’ out. But he killed the black man.”

Always my father had told that story as an act of heroism, bravery, self-sacrifice. When I interviewed and recorded him those few months in 2015, though, he spoke to a different version of his son than the one he’d first told the story decades earlier. He offered a defense those earlier tellings never found necessary. Uncle Phil “just told it kind’a like matter of fact. He was just doin’ his job. It was either him or the black man. He didn’t act like he was proud of doin’ it. He just acted like it was somethin’ that was necessary to do.”

When Phil Gilmore patrolled the streets of Americus on foot and saw a “a black boy or man was on the sidewalk,” my father said, “he’d tap him on the leg with his night stick, make him get off on the street.” Frequently my father followed such depictions by saying, “That’s just the way things was.”

Back in 1977, in 1980, these stories carried no qualifiers. The defenses began around the time my father became too ashamed to use “the n-word” around me. One Saturday morning in 2015, he said, “As a boy, I just said and thought the things the people around me did. I did that absolutely. I’m sure there’s some racism in me. It’s not extreme. I’ve had a lot of black friends. I can be friends with a black man.”

Then he started talking about Emmett Tookes. Tookes remained always with him. Perhaps it’s wrong to credit my five year old self with my father’s cessation of racial slurs, for Emmett Tookes survived as some sentry in my father’s conscience.

Once Grady let Leslie, the boy who’d grow up to become my father, have his own calf, a white Hereford, and the boy and the calf play-fought all the time. He’d grab the calf by his horns, called him his buddy, tried to throw him down. He never succeeded. Usually the calf threw him instead.

One day he decided he’d impress his daddy and talked him into letting him shoot a pig for butchering. He already had his own .22 rifle. He took aim and he hit the pig, but he didn’t hit him right and the pig broke his heart. The pig ran crooked, squealing and screaming around the pasture, and his daddy and Emmett Tookes had to chase that pig down and finish the killing.

I find notice in The Americus Times-Recorder, September 23, 1920, that Phil Gilmore’s gray mare mule, 15 years old and 1400 pounds, and his dark bay horse mule, 20 years old and 1200 pounds, were “lost, strayed or stolen.” If I find them, I’m supposed to “take up and notify” P.C. Gilmore, whose phone number is 748. A year later, The Macon News reports he declares bankruptcy.

I searched for years without finding record of Phil Gilmore’s killing a man. Then, suddenly, there it is: The Macon Telegraph, Sunday morning, May 5, 1929: “Negro is Killed in Liquor Raid.” His name was Henry Clark. He was 50 years old, a political activist.

My great-uncle and the chief of police raided an alleged “speakeasy,” a barbershop and poolroom on Cotton Avenue in Americus at the height of Prohibition. Gilmore and an officer named Glawson came through the back door as the police chief and a lieutenant came through the front.

“As Officer Gilmore called to a number of Negroes to ‘Stand back!’ Clark rushed upon him and attempted to seize the officers revolver. A desperate struggle for possession of the wapon followed and other officers in the party rushed to the aid of Gilmore.” [Several sics.]

Chief John Newton Worthy said that as he’d come upon the struggle, “Clark had all but wrestled the pistol from Gilmore’s possession.” He said he’d asked “the negro” to stop struggling, and Clark said, “I’ll die and go to hell!”

Said the Telegraph: “At this point Gilmore was forced to release the weapon momentarily and Worthy seeing his brother officer in imminent danger fired. Almost simultaneously another shot was heard, the weapon over which the two were struggling having been discharged. One bullet entered Clark’s chest inflicting a wound from which he died before medical attention arrived.”

Click here for your tickets to the upcoming book launch of The Culture Wars of Warren Folks.

The story ended with a note that Henry Clark had been “active” in “Negro political affairs” in Americus “during many years.”

A news brief dated my birthday, 30 years before I was born, June 24, 1944, says, “Phil Gilmore, who served as police officer for many years when the late Will Walters was chief has returned to Montezuma to fill the position of chief of police. He left Montezuma in 1922 and has been living in Americus.”

I’ve asked more than a dozen contemporary black residents of Macon County with the last name of Tookes if they’re descended from an Emmett, but none of them say they’ve heard of him. I’ve scoured hundreds of records of Macon County Tookeses, Eddie and Erice and Louhazel and Zollie, but I find no Emmett.

In the spring of 2019, my father had been in the cardiac ward at St. Vincent’s Hospital for four days. Disoriented, he couldn’t tell day from night. He’d only live another four months.

I’d been sitting next to the hospital bed for some time. He hadn’t said a word for half an hour, when he turned his head my way, looked up at me and said, “Didn’t you tell me that you helped pay to bury Emmett Tookes?”

When I was born, in 1974, my grandfather Grady had been dead almost 40 years, and my father was 50, four years older than Grady had been when he’d died. My father could never remember if Emmett Tookes kept working for the family after Grady Gilmore’s death.

“Emmett Tookes?” I asked, wondering if I’d heard him right.

“Didn’t you tell me that?” he asked, his old, old eyes questioning mine.

“Emmett Tookes died a long time before I was born,” I said.

He looked puzzled.

“Do you even know where he was buried?” I asked. “Was his grave marked?” I wanted desperately to know. I’d asked these things before, many times. Recently my father had started remembering songs he hadn’t heard for 75 years. His memory was newly upturning long buried bodies.

“No,” he said. “He was lucky to get buried at all.”

I wish I could talk to Emmett Tookes, that we could build a new dinner table together, for both of us, though I think how if I were him, I’d hate Grady Gilmore’s grandson’s guts. Under “Local Briefs” in the September 9, 1920 edition of The Americus Times-Recorder, I find notice that “Mrs. Phillip Cook Gilmore, of Montezuma, spent the afternoon in Americus yesterday, shopping.” Just that one sentence. What was Emmett Tookes doing that day?

Oh damn im hooked! Yes!