My dear, dear friend, Ken McCulough, with whom I worked on four stage shows at FSCJ DramaWorks, including his very last one, is gone from us. 9:34 Thursday morning. The world is different now. I wrote this story, just two years ago, when he retired.

1. “We Have Come Here in Search of an Author”

The six characters enter and stop by the door at the back of the stage. A tenuous light surrounds them, almost as if irradiated by them.

THE FATHER is a man of about 50. He has blue, oval-shaped eyes, clear and piercing. THE MOTHER seems crushed and terrified as if by an intolerable weight of shame and abasement. THE STEP-DAUGHTER shows contempt for the timid half-frightened manner of the wretched BOY (14 years old, and also dressed in black); on the other hand, she displays a lively tenderness for her little sister, THE CHILD (about four), who is dressed in white. THE SON (22) tall, severe in his attitude of contempt for THE FATHER, supercilious and indifferent to THE MOTHER. He looks as if he had come on the stage against his will.

The Manager [rudely] Eh? What is it?

Door-keeper [timidly] These people are asking for you, sir.

The Manager [furious] I am rehearsing, and you know perfectly well no one’s allowed to come in during rehearsals! [Turning to the CHARACTERS.] Who are you, please? What do you want?

The Father [coming forward a little, followed by the others who seem embarrassed] As a matter of fact . . . we have come here in search of an author . . .

The Manager [half angry, half amazed] An author? What author?

The Father Any author, sir.

2. “The Value of Being Together”

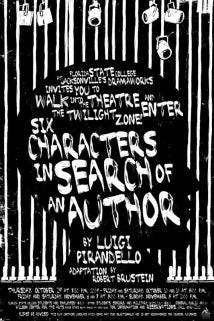

Luigi Pirandello’s 1921 play Six Characters in Search of an Author is complicated. Absurd. Existential. Postmodern before postmodernism. I’d been teaching at Florida Community College at Jacksonville for two years when my wife and I saw the FCCJ DramaWorks production. Already I loved the play, but I’d never seen it. I’d read it, but plays are written to be performed. I couldn’t believe they pulled it off. I couldn’t believe they’d even tried it.

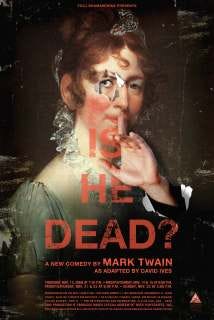

The year before, DramaWorks director Ken McCulough had staged the newly discovered Mark Twain play Is He Dead?, which I bought and read. Now, 14 years later, I’ve seen almost every FSCJ – the “Community” became “State” – play in my time at the school and read or re-read them ahead of time.

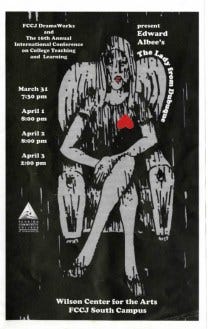

Now Ken’s retiring. He’s been at the college for 28 years. He’s directed 55 productions. He’s directed 12 Angry Jurors and Lanford Wilson’s Book of Days, Carousel and Cabaret, the Southern Gothic Holy Ghosts by Romulus Linney, James and the Giant Peach and David Mamet’s Revenge of the Space Pandas, Edward Albee’s The Lady from Dubuque with Albee himself in attendance, Much Ado About Nothing and Twelfth Night, Dylan Thomas’s Under Milkwood and You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown. He’s directed plays by Gina Gianfriddo, Ethan Coen and me.

When Ken asked me to adapt one of my books for the stage, what was already a friendship blossomed into a wonderful series of collaborations. It takes magic to take a cast from script to blocking to full production and it took courage for Ken to work with the material I brought him. In 2017, we collaborated on Stalking Ottis Toole: A Southern Gothic, an adaption of my 2015 book about the phony serial killer who bragged (and lied) about necrophilia and cannibalism.

Stalking Ottis Toole: A Southern Gothic, 2017, from a review by Dick Kerekes and Leisla Sansom

As theater critics Dick Kerekes and Leisla Sansom wrote, “The program included a warning that the play is not suitable for audiences under 18 years of age. While well written, we don’t anticipate it will become a favorite of community stages, as it touches upon subjects which include arson, cannibalism, child molestation, necrophilia, and random murder. However, we found it a well-executed and thought-provoking evening of theatre.”

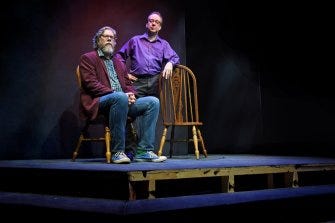

Tim Gilmore and Ken McCulough, discussing Repossessions: Mass Shooting in Baymeadows, photo by Bob Self, courtesy The Florida Times-Union

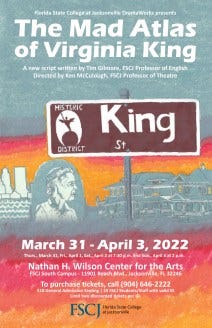

Two years later, Ken directed Repossessions: Mass Shooting in Baymeadows, a monologue-based documentary theater piece I wrote about the aftermath of that 1990 event (until 2016 the worst mass shooting in Florida), told entirely in the words of survivors and victims’ family members. That was Ken’s 50th production. In 2021 I wrote the “Covid Monologues” to accompany music and dance for his variety show A World Distanced. After Repossessions, which prompted heightened security and weighed heavily on everyone who worked on the play, Ken said he wanted to do one more full production, “but something lighter this time.” So now, Thursday evening, March 31, 2022, is opening night for The Mad Atlas of Virginia King.

Virginia King harassed the wealthy and powerful for information. They hid from her when they saw her coming. She marched daily across Riverside, Downtown and the rest of the city, took buses, made her income from magazine subscriptions and government assistance, spent all her money on bus fare, paper, film, newspapers, bread and lunchmeat. With her Kodak Brownie camera, she took countless photos of buildings about to be demolished. The photos are crooked and blurry because she couldn’t slow down to snap the picture. Her facts are often non-factual. She wrote in unreadable lists and gave chapters titles like “These Were Built, Organized, Changed Hands or Demolished Certain Dates.”

In his 2002 eulogy, Revered Tom Are, then pastor of Riverside Presbyterian Church where Virginia was a lifelong member, said, “It seems to me that Virginia King served as something of a prophet in our town. Here she was, circumstantially alone, but constantly reminding us of the value of being together.” In a recent email, Ken told me, “Virginia won’t be taking the bus this time.” Figuratively (or not), he said, “She (and we) are going to dance down Riverside Avenue!”

3. Preacher’s Son

Ken McCulough’s father was a preacher. And preaching is performance. It’s theater. Growing up in rural Arkansas was hard enough without being gay in a fundamentalist Baptist church with your father in the pulpit. The two grew closer in the last years of Ken’s father’s life.

Against the grill of that great wide tank of an automobile in the late 1960s, Ken leans into his father. He called him “Daddy” all his life. His father faces forward, the arm with the wristwatch clenching the opposite wrist, short-sleeve white button-up shirt and tie, big black-frame glasses. He stands stiff and still and straight, doesn’t accommodate Ken’s leaning into him.

But they came to a place of reconciliation, of gracious understanding. “We were not very close or affectionate when I was growing up,” Ken later said, “but he was often stressed and anxious working several jobs to provide for his family and serving the Lord.”

About that photograph, Ken jokes about his “long arms and girl shoulders and fangers,” [sic] about popping his hip away from his Pop, though “I still tilt my head in an alluring fashion when being photographed for Vogue or GQ.”

Ken’s partner’s father was a minister too. Don Yanik, professor emeritus and retired chair of theatre at Seattle Pacific University, laughs and says, “Isn’t it strange that two minister’s kids would get together?” to which I say, “Not necessarily.” Ken and Don have known each other for 40 years, in which time they both left the church, then found their way back to it. For Don, that came through the experience of restoring The Kilns, C.S. Lewis’s house in Oxford.

Don says, “The cast is kind of like your congregation.” Both men had the role of preacher presented as template from early years. “Both of our fathers were kind of always on,” Don says. “They had to sell their sermons, their faith. They had to perform.”

When we included excerpts of David Bowie songs in Stalking Ottis Toole, Ken recalled teenage years when there was nothing to do in Arkansas, but David Bowie made you feel not so alone, riding around in pickup trucks listening to “Rebel, Rebel.” Singing along, “You got your mother in a whirl. / She’s not sure if you’re a boy or a girl.”

Programs from the 1980s show Ken acting in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and singing, young, jubilant, in turtleneck and denim jacket, hair and eyebrows full, in Jacques Brel is Alive and Well and Living in Paris, the cast recording one of Bowie’s top 25 favorite albums, the off-Broadway ’68 show running for four years, film adaptation in ’75.

When curtains came down on Stalking Ottis, Bowie came back: “Rebel, rebel, how could they know? / Hot tramp, I love you so!”

4. “You’re a Director”

On October 5, 1988, The Commercial Appeal of Memphis, Tennessee headlined a review, “‘Tales from Hollywood’ Took Circuitous Route to MSU Stage.” The Center Theatre Group of Los Angeles had commissioned British playwright Christopher Hampton’s play in 1982 and in ’83 the play was restaged in London.

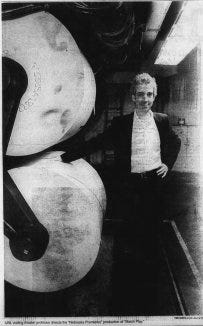

Three years later, “a young Arkansan working in Seattle theaters as lighting designer, master electrician, stage manager and director” saw the play. In ’88, Ken McCulough, the “young Arkansan,” selected it to direct at Memphis State University (now the University of Memphis), “as requirement for his master of fine arts in directing.” Ken had just directed Arsenic and Old Lace in nearby Collierville, but Tales from Hollywood was a bold and ambitious choice.

Standing in the “campus lighting booth,” 28 year old Ken said, “The play isn’t done that often, mainly because it’s so complex and so difficult to do and has such a huge cast.” Telling the story of German writers who fled Nazi Germany for California, the play consists of 22 short, quick scenes. Characters include Bertolt Brecht, Thomas Mann, German playwright Oedeon von Horvath, and Hollywood stars Johnny Weismuller, Greta Garbo and Chico and Harpo Marx.

Ken directed other plays about writers like Howard Brenton’s 1984 Bloody Poetry, centered on Romanticist poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein, and poet Lord Byron, the primordial prototypical rock star.

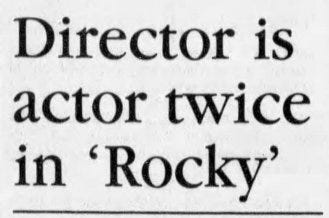

In 1990, Ken played Brad, “the square hero” in A Rocky Horror Picture Show, then took over the role of drag queen Frank N. Furter when the original actor took a role in Florida. “Those are some mighty big pumps to fill,” Ken told reporters.

“With his flaming carrot top, McCulough has the air of a wide-eyed teenager,” wrote Donald La Badie of The Commercial Appeal. “‘The thing is,’ he said, sipping a Coke and pulling at an outsized earring, ‘I hadn’t been on a stage in eight years when I did Brad. I can’t remember ever having been so nervous.’”

Ken described how his singing style differed from that of Mark Chambers, the actor he was replacing, and where those styles came from. “He’s a devil for dialogue improvisation on stage, but his vocal training was classical and he prefers to stick close to the music. I got my experience in rock and roll and gospel. I like to improvise.”

The split between Ken the actor and Ken the director, he said, was starting to make him feel schizophrenic. “I mean, when I’m on stage, part of me is out in the audience evaluating the performance. How am I doing? Did that character miss his cue? Is that light about to crash to the floor? Of course the actor part of me is struggling to stay in character.” That year, however, Rocky Horror got Ken nominated for a Memphis Theater Award for Best Actor and won him awards for Best Director and Best Musical.

He’d received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, where he first met his partner-to-be Don Yanik. When Don took the position at Seattle Pacific, Ken directed and worked lighting in Seattle. Despite the excitement of that period, Don recalls, “I insisted he leave Seattle to get his graduate degree.” He did.

At Memphis State, Ken thought he’d focus on lighting, but faculty members staged an intervention, telling him, “You’re a director.” Don says, “He was always so gifted, brilliant even, if I may use that word. His insights into human interaction are spot-on. It’s a natural thing for him.”

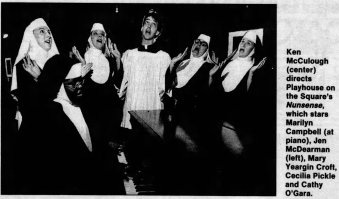

A September 30, 1993 story in The Germantown [Tennessee] News reported on a Sunday School group who’d attend Ken’s production of Jesus Christ Superstar. The group was to take notes, then pass a church test. Church member Larry Groh “asked class members to recall the controversy created by the musical when it was first performed, noting that the play caused people to re-evaluate their beliefs regarding the role Christ played in the early church.” The News noted that McCulough was “the son of a minister,” as it had when Ken directed and performed in the musical comedy Nunsense in 1991.

Ken took over as professor of theater and director of FCCJ DramaWorks in 1994. Technical Theater Director Johnny Pettegrew had left Jacksonville University for FCCJ the year before, lured by the prospect of helping build a theater program and watch the brand new Nathan H. Wilson Center for the Arts come up from the ground. Beth Harvey became assistant director of the Wilson Center in late ’95.

The college had presented plays in the Brutalist G-Building in the center of South Campus and at Theatre Jacksonville at the historic Little Theatre in San Marco. Beth, who’d worked with Bob White at Theatre Jax to produce Shakespeare in the Park at Metropolitan Park downtown, took over as Wilson Center interim director twice, once while undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer, when the first two directors lasted a year and four months, respectively.

Beth remembers first meeting Ken. He was gracious, gentle yet demanding, ambitious but made hard work look easy. “He was just like he is now, just younger,” she says. “He’s been remarkably consistent.” She says he was always willing to take on challenges and introduced the college to several shows not already widely known.

Ken’s production of Cabaret was the first show on the Wilson Center’s main stage. The first show in the studio theater was his production of Timberlake Wertenbaker’s Our Country’s Good, a play about the colonization of Australia as a penal colony, soldiers directing prisoners with brutality in a play within a play, Irish playwright George Farquhar’s Restoration comedy The Recruiting Officer written in 1706.

Standing in late 1960s period costume before dress rehearsal for The Mad Atlas, Ken recalls “all the accents actors had to get down. Scottish, Irish, Australian, Aborigine.”

Johnny Pettegrew sits behind the sound console, his beard having grayed more than his hair in the last three decades. Ken reminds him of all the sand Johnny trucked in for the scene on the beaches where Sydney stands now. The two of them laugh about it. “There’s still sand in this building from it,” Ken says. Beth stops by, reminisces, agrees. “Yeah,” she says, “the sand is still in the building.”

In March 2000, Ken directed a new play in Lincoln, Nebraska two months after the death of playwright William McCleery. Ken had taken a sabbatical at FCCJ to accept a one-year visiting professorship at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. McCleery — playwright, journalist, professor emeritus at Princeton and Nebraska native — had won a contest to have his new play,Match Play,open as the inaugural production of “Nebraska Premieres,” a collaboration between the Nebraska Repertory Theatre, the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Department of Theatre Arts and the Nebraska Arts Council.

Ken had spoken with McCleery twice and sent him audition tapes. The playwright was scheduled to attend the premier. Though his death shocked Ken, Ken said winning “a playwriting contest in his home state” was a good way “to make an exit.”

5. To Make Him Proud One Last Time!

Mike Von Balsan, Jr. knew he “had to audition, if for nothing else, to tell Ken ‘thank you’ in person for how he poured into me.” Mike plays Rufus, Jr., Virginia’s brother, in The Mad Atlas. His embodiment of this strange character, bearded and always dressed in shabby three-piece suits, is mesmerizing. Mike steps into Rufus, Jr. after a 23 year stage absence.

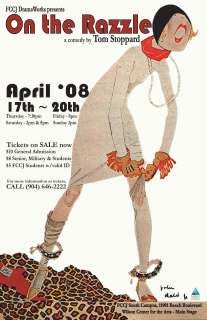

Mary Cumpton, who plays Virginia, says it “means the world” to come back and act for Ken again. When she attended FCCJ as a theater talent grant student from 2006 to 2011, she was cast in every show, including David Lindsay-Abaire’s Wonder of the World, the Tom Stoppard play On the Razzle and Holy Ghosts.

“Ken’s expectations were always high,” she says, “which kept all of us constantly reaching for a higher level of professionalism and performance. He would take time to work one-on-one with students who were struggling with a show in order to allow them to grow. He did it without judgment. He would laugh at our silliness and inside jokes, but always knew when it was time to buckle down and get serious. He got to know us personally. He cared about us.”

theater students Misty Liberty and Kate Dial with the infamous Ken McCulough cutout, 2016

Mike worked with Ken in 1995 and ’96, when Ken was still new to the college. Mike performed in those very first productions, Cabaret and Our Country’s Good. He says, “There was something both intimidating and inviting at the same time. I remember Ken being very specific about what he wanted. And it wasn’t until a couple of shows in that I realized his specifics created a vision for the entirety of the show.”

Mike and Mary both testify to how much Ken cares about his student actors and how naturally actors respond and reciprocate. “You immediately wanted to do right by him,” Mike says, “because you knew he cared about you as a person and was pulling the best out of you. I remember him saying, ‘Acting is what you do when you aren’t speaking.’” Mary adds, “Being able to stand on the main stage with Ken in his very last production at FSCJ is magical! And emotional. I’m so extremely honored and I hope I make him proud one last time!”

6. “Poured Into”

I’ve always felt a theater a gloriously haunted place. Felt it in my marrow. Not supernaturally. Culturally and psychologically and artistically and acoustically. Every opera house has its phantom. Acoustics reverberate strangely from backstage to the balcony, from above the heads of the audience to the prop room, where cut-outs of strange unnamed characters stand open-mouthed and frozen behind candelabra, and mitres and staffs, and sickles and scythes, bubblegum machines and books, dishware and puppetry.

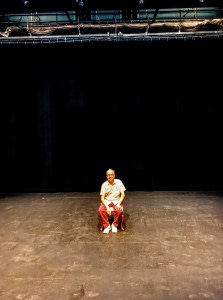

I can’t quite believe the echoes of every voice spoken in this theater have dissipated. And the seating seen from the stage in the Black Box Theater resembles a typewriter. Everything I could type on its keys, every laugh and heartbreak and harmony of joy and primal scream, rests there where the next audience will take its seats. They’ll dip themselves into the mythos.

Ken McCulough gave himself to these spaces, or as Mike says, “poured into” his students here, let in characters to search out authors, filled the body of this building with his soul, year after year, from the Wilson Center’s inaugural production to Virginia King’s Mad Atlas. It’s not just Mary. Or Mike. Or the dozens of students who’ve worked for Ken the previous 28 years and came back to audition for this final production. All of us want, once again and finally and originally, to make Ken proud.

7. The Reality of Illusion

The Father [irritated] The illusion! For Heaven’s sake, don’t say ‘illusion.’ Please don’t use that word. It’s particularly painful for us.

The Manager [astounded] And why, if you please?

The Father Oh, it’s painful, cruel, really cruel. You ought to understand that.

The Manager But why? What ought we to say then? The illusion, I tell you, sir, which we’ve got to create for the audience…

The Leading Man With our acting…

The Manager The illusion of a reality…

The Father I understand. You however, perhaps, don’t understand us. Forgive me! You see…here for you and your actors, the thing is only — and rightly so…a kind of game.

The Leading Lady [interrupting indignantly] A game! We’re not children here, if you please! We are serious actors.

The Father I don’t deny it. What I mean is the game, or play, of your art, which has to give, as the gentleman says, a perfect illusion of reality.

The Manager Precisely — !

The Father Now, please consider the fact that we [indicates himself and the other five CHARACTERS], as we are, have no other reality outside of this illusion…

It’s a beautiful story, Tim. His death is too early, and it’s terrible. I’m glad you were able to write this celebration of Ken’s life and work before being hit by the grief of his passing. I know there’s room for you to write more about Ken now that he’s gone and in light of those feelings, but this stands here on its own before that, and I’m glad we have it.