Trinity Christian Academy: Bob Gray’s Office / Tom Messer’s Office

(Or, A Half-Century of Covering Up Child Sex Abuse at Trinity Christian Academy)

Thank you for reading Tim Gilmore’s deadpaper. Perhaps you know my writing from my 23 books, perhaps from my 761 nonfiction stories at JaxPsychoGeo.com, or perhaps you’ve no idea why you’re here and reading this very sentence. I’m still aiming for 10 percent of this newsletter’s readers to be paid subscribers, so please at least think about becoming one if you’re not. Either way, I’m grateful for you.

1. Asking Victims to Apologize

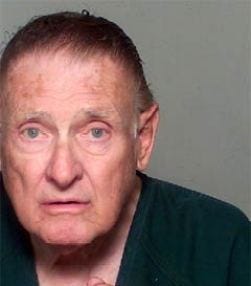

Ann remembers sitting on the preacher’s lap and eating ice cream when she was six years old. She understood that Bob Gray was an important man.

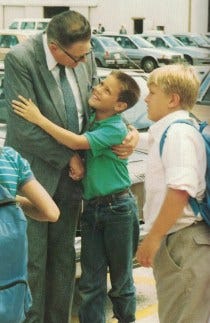

Gray seemed grandfatherly. He held her hand on walks and, time and again, sought her out from hundreds of other children to sit on his lap.

When she was in third grade, he started calling her out of her Trinity Christian Academy classroom to meet him in his office. He’d tell her how pretty her eyes were. When he started to do strange things, things that made her feel afraid and sad, she thought, “I guess he must really love me a lot.” He molested her for years.

In 1992, when Ann was 21 and already married, her mother heard odious allegations against Gray and mentioned them to Ann. It was the first time Ann ever told anyone what Gray had done to her.

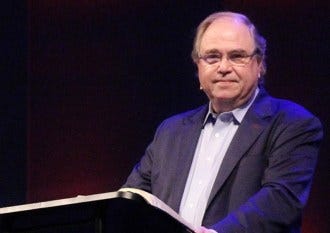

Then Tom Messer, primed to take over leadership of the church and school when the coverup of Gray’s decades of child sexual assault came to light, asked Ann and her husband to meet with him personally. He asked for details and Ann supplied them. She wept deeply. She’d believed Bob Gray had done those things to her because he loved her.

Messer said another victim had admitted “only” to Gray having “French kissed” her and “that was all there was to it.”

His response made Ann feel that her allegations against Gray were exorbitant and ridiculous, that the church wouldn’t take them seriously, and that church leaders found Gray’s “French kiss[ing]” children trivial.

Ann felt she had disgraced a great man of God. She had betrayed the mighty pastor who had loved her so dearly.

Immediately thereafter, Tom Messer arranged for Ann to meet with several deacons to recount her allegations all over again. She agreed to the meeting, but when she arrived, she was stunned to find herself seated alone and forced to wait in Bob Gray’s office.

She waited and waited. Finally, instead of the group of deacons, Bob Gray himself walked into the room, and Ann found herself alone with him in the same office where he had assaulted her for years.

Gray sat down in a chair touching hers. “He did not speak a word,” Ann says. “He just held his head low.”

She felt terrified and vulnerable, but she also felt guilty. She had brought such sorrow to such a great man. She’d betrayed him.

So she wept and told him she was terribly sorry she’d told anyone what he had done. Still he said nothing. She felt “the guilt of a woman who had been caught in an adulterous relationship,” and as she cried and apologized, Tom Messer and several deacons entered the room.

They came to her at her weakest moment, but offered her no comfort. Instead, they used her weakness to defend Bob Gray. In his presence, in his office, once again, they asked her to state her allegations.

They called her words a “confession” and asked her if she thought her “confession” should be defined as “molestation” on the part of a pastor who had loved her. That pastor stood sadly before her and awaited her answer. Thus shamed, she said no.

The next day, Tom Messer approached Ann at church and asked her if she thought it would be best to apologize to Bob Gray’s wife. Thus shamed, she said yes.

2. “A Very Important Part in All Our Lives”

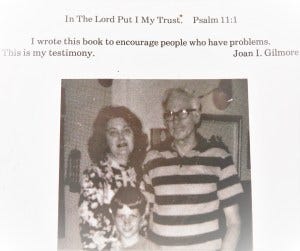

“God led us to Trinity Baptist Church,” my mother wrote in 1981. “The church played a very important part in all our lives.” I was seven years old then. When I came home from school each day, I’d see my mother’s typewriter on the kitchen table. A boy at church asked me if my mother was a writer. Her book was 23 pages long and named for a verse in The Book of Psalms: In the Lord Put I My Trust.

She wrote the book as her “testimony,” describing her first marriage to an abusive alcoholic who abandoned her and their three daughters, my older sisters – I came from her second marriage – while she was bedridden with illness.

She wrote of how her youngest daughter, my sister, would take “a long time coming to the car” after church services on Sunday mornings. “I noticed she was going around to the back of the church and waiting for our pastor, Bob Gray. He noticed her standing there and would gently put his arm around her. She did this for several months after each church service. Brother Gray knew what the problem was and that the little hug from him meant a lot. She was only eleven and was missing a father’s love.”

While she interrogated herself repeatedly, wondering if she’d hidden it from herself, my sister doesn’t believe she was one of Gray’s victims, one of, as current Trinity Pastor Tom Messer puts it, the “20 or 30 or 40 victims, however many there were.” (Dennis Cassell, Trinity Christian Academy’s first football coach, later said he believed there were hundreds.) She so easily could have been; she was exactly the kind of child Gray targeted.

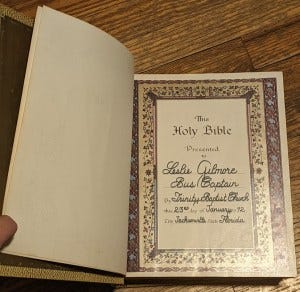

“I got a job in Trinity Christian Academy,” my mother wrote, “working in the daycare” with three year olds. At Trinity Baptist Church, my mother soon met a church deacon named Leslie William Gilmore, the man who would become my father. He had also been a “bus captain,” whose mission was to scout neighborhoods during the week and find people, particularly children, to pick up on Sunday mornings, in one of Trinity’s many former school buses, and bring to church.

My mother had also met with Pastor Bob Gray to ask if, according to the Bible and the church’s authority, she could be divorced from the abuser who’d left her. Now she met with Gray to ask, as she put it, if “I was free to ever remarry.” Trinity’s pastor granted her permission to marry the man who would soon become my father.

3. Tom Messer’s “Draft Statement”

In 1992, the phrases “indiscretion” and “neither sexual nor immoral” were repeated throughout the congregation and across the campus compound.

In 2007, a Jacksonville TV news station obtained a copy of a tape recorded just before Gray’s arrest in 2006. Though Trinity, under Messer’s leadership, released a statement after Gray’s arrest that the builder of Jacksonville’s first “megachurch” did nothing wrong and that nothing in Trinity’s records showed any “indication of a cover-up,” the pre-arrest tape demonstrated otherwise.

On the tape, an anonymous woman says, “People sitting in Trinity still do not believe that there is anything that Gray ever did [that was] sinful.”

Then she speaks directly to Messer, referring to the 1992 coverup: “Remember, Tom, it was an ‘indiscretion.’ It was not of a sexual nature,” and then she tells him, “That is not true.”

Messer replies, “I’ve never doubted that what he said that first night was inaccurate. I’ve never doubted that, and I wouldn’t sit here and say that today.” He calls the statement Gray made to the church about an unnamed indiscretion, after which the church gave Bob Gray a standing ovation, “erroneous.”

To an anonymous man on the tape, Messer says, “You want the erroneous statement that was made by Brother Gray to be corrected.”

The man tells Messer he wants him to admit publicly to the church that Gray’s 1992 statement was a lie and to be truthful to the congregation that Bob Gray sexually abused children.

Messer says, “I have a draft statement.”

Messer’s proposed date for his public admission of Bob Gray’s pedophilia was May 21, 2006, but when Bob Gray was arrested on May 19th, Messer backed out of the deal.

Though Gray died just before jury selection for his trial, attorney Adam Horowitz, who’d filed six civil suits against Gray, said the tape “establishes that Tom Messer and other leaders were in conspiracy with Bob Gray to conceal the truth from the parishioners and cover up wrongdoing.”

4. Trinity’s “Family Squabble”

In June 2016, Tom Messer, the current pastor of Trinity Baptist Church, shook my hand and invited me into his large comfortable book-lined office. It’s the same office in which Bob Gray sexually assaulted children for decades. (It’s the same office from which Trinity covered up other instances of student sex abuse, as late as 2019.)

We sat on couches across from each other. He asked me about myself, asked me when I was a student at Trinity Christian Academy.

“When I first heard what you wanted to talk to me about,” Messer said, paused, leaned back into the couch and threaded his fingers together on top of his head, “my first reaction was, ‘Sigh.’”

In the course of our discussion, I asked him, “How can a man preach about Jesus and —” When I found myself at a loss for words, Messer said, “— molest children.” That’s true, but I had read the 500 pages of legal depositions and the words I had in mind were unspeakably more specific.

Messer said that Jesus died for all our sins, no matter how trivial, no matter how heinous. Because all of us are sinners, no person’s sin is worse than another’s. Sin is the condition of mankind. He told me, “God uses broken people.”

Several times, Messer said, “There are so many things I know that I can’t say.” Several times he started to say something, then stopped and said, “I can’t say that.”

Believing confession to be a basic human need, I’d hoped, while I’d not expected Messer would actually meet with me, that he might feel relieved to get something off his soul.

Bob Gray built Trinity Baptist Church. Before Gray, Trinity was another miniscule Southern congregation of which towns like Jacksonville had thousands. Gray made Trinity Jacksonville’s first “megachurch.”

I’d told Messer I was writing a book about Gray and Trinity and the coverup. He told me he didn’t think many people would care. “If you don’t throw wood on the fire,” he said, “eventually the fire goes out.” What the news media and its viewers and readers hadn’t understood, Messer said, was that Trinity was a family, and that what had happened at Trinity was “a family squabble.” No one outside of the family needed to be concerned.

I asked him if he thought anyone should have called the police or state authorities. He said something about people choosing not to do so.

“So no one was actually told not to call the police?” I asked. He rubbed the corners of his eyes and looked thoughtfully at the far wall of the office. “Did you ever think you should have called the police?”

He said there were so many things he knew that he just couldn’t talk about. All I could do was say, “I can’t imagine how anything you might know could impact that question.”

Tom Messer leaned determinedly forward, elbows on his knees. “Look,” he said, “I’ve been very charitable to you. I’ve been more transparent than I’ve even been comfortable being.” He rubbed his knees and started to stand.

“I feel no need to justify anything that I have done,” Messer told me. “All the justification that anyone needs has been accomplished in Christ’s death on the cross.”

That last sentence is complete and utter disregard for the victims. It’s a cop out.

I’m going to try to search Florida Statutes to see if preachers or other church are mandated reporters of such accusations.

Wow. That last sentence is frightening.